Melburnin’ JULY 2014

The depth, diversity and size of the University of Melbourne’s museums and collections, some dating from the earliest years of the institution’s establishment in 1853, will be in focus during its biennial Cultural Treasures Festival (26 – 27 July, 2014). Of great cultural significance and including individual heritage objects, the official number of University collections now stands at thirty, with a further eight sub-collections that are managed by other collections, or sit within ‘parent’ collections. An integral part of this year’s program, Radicals, Slayers and Villains: Prints from the Baillieu Library at the Noel Shaw Gallery (until 3 August, 2014), is curated by Kerrianne Stone, the Curatorial Assistant of Special Collections (Prints).

The Baillieu Library Print Collection has developed over time to comprise over 8,000 items dating from the late 15th century to the 21st century, and with a particular strength in European old masters. It owes much of its scope to the English-born doctor (John) Orde Poynton, AO, CMG (1906-2001), who donated some 3,000 prints and 15,000 books from 1959 onwards, the year the library was completed. J. Orde Poynton was a pathologist who joined the British Army in World War II, and was captured by the Japanese in 1942. He became one of the many POWs incarcerated at the infamous Changi Prison, which led to him being brought to Australia to recover from its privations. Poynton reportedly packed up portions of his gift to the Baillieu in cartons intended for blood transfusion bottles, and that, coupled with his profession and experiences in the war, act as something of a metaphor for the often lurid and gruesome contents of the present exhibition.

The donated prints are believed to have been the passion of his father, Frederic John Poynton (1869-1943), who was noted for his study of rheumatism in children, and was elected president of the British Paediatric Association (BPA) in 1931 (now the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health). The elder Poynton was awarded the Dawson Williams Memorial Prize for founding the Heard Homes for convalescent rheumatic children in London, and maintained a first-class cricket career for Somerset County between 1891 and 1896. In seeking to build a collection in which all printing techniques would be exemplified, the majority of the works were purchased between 1924 and 1939, a proportion from well-known dealers in London. Many of the works were vetted by experts at the British Museum such as A.M. (Arthur Mayger) Hind (1880-1957), Keeper of the Department of Prints (1933-45), whose specialty was in Italian engravings. The book collection was the principal focus of J. Orde Poynton, particularly the then-neglected areas of Greek and Roman classics.

Stone has brought together sixty-six works and twelve illustrated volumes replete with provocative scenes of degradation, revenge, despair, violence, institutionalised torture, corruption, heroism and a deeply ambivalent relationship on the part of the individual towards contemporary society. She makes the point that the exhibition terminology is flexible, and will probably be determined by the attitude of the viewer, “…we have applied the categories of ‘radical’, ‘slayer’ and ‘villain’ loosely. It soon becomes apparent that may of the individuals depicted here transcend such terms and are complex in both context and perceptions”. The emphasis is on controversial mythological, Biblical and historical figures whose (often invidious) exploits have challenged the status quo, and helped shape world events and perceptions across many centuries in the development of Western art and culture. These particular characters, and the dramatic potential their lives encompassed, have inspired artists, appealed to their patrons, and captured the imagination of the wider public throughout the ages, resulting in a proliferation of interpretations.

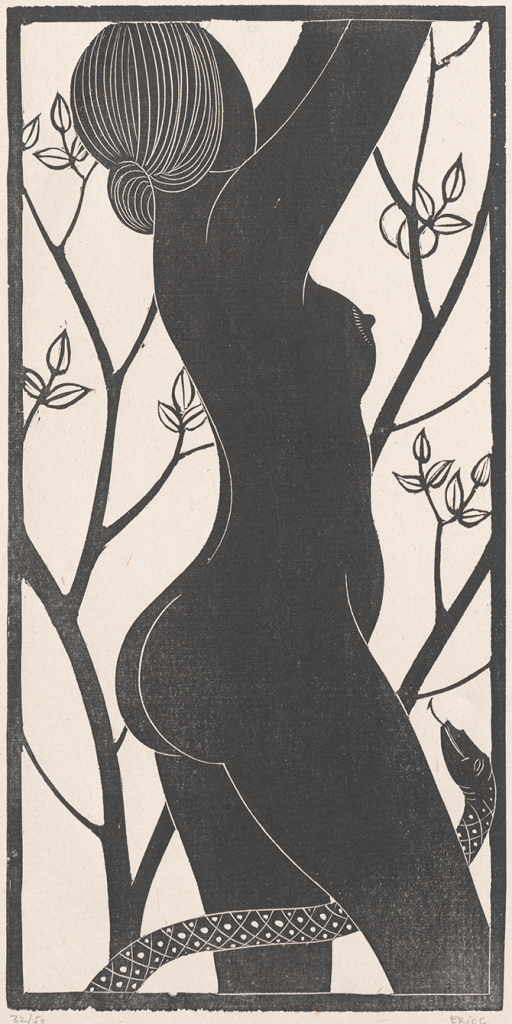

The exploits of women – as moral exemplar, feared aberration, fraught object of desire, and cautionary tale – are prominent in the exhibition. Eric Gill’s elegant and voluptuous engraving Eve (1926) is unambiguous in its erotic content, placing the snake (traditionally identified as Satan) directly between her legs. The deeply religious Gill (1882-1940) converted to the Roman Catholic faith in 1913, but was notorious for his bizarre personal morality. He documented his obsessive sexual life, which he appeared to rationalise as being ‘an aspect of God’s glory’. This encompassed numerous extramarital affairs, including incest with his sisters and his two eldest daughters. The imagery of the serpent, and its association with female sexuality, is reiterated with the suicide of Cleopatra (VII Philopator) on August 12, 30 BC, a perennially popular subject for artists. In his work Cleopatra With Two Asps and Cupid (c.1510-30), Giacomo Francia (c.1486-1557/67) depicts the doomed queen as a Venus-like figure toying with the instruments of her death in a forest landscape, as the classical god dances beside her.

(Arthur) Eric (Rowton) Gill (English, 1882-1940), Eve (1926), wood engraving; impression 32 of 50, block 23.7 x 11.7 cm, sheet 35.9 x 21.3 cm, (Purchased, 2012).

Bartolomeo Coriolano (c.1599 -c.1676) delivers his rendition of the notoriously awkward mother-daughter dynamic in Herodias and Salome with the head of St. John the Baptist (1632), and its messy denouement. Predatory figures of authority menace the unsuspecting wife of Joachim in Susanna and the two elders (c.1508) by Lucas van Leyden (c.1494-1533). Van Leyden positions the two men in the foreground, exploring the moment of stillness and conspiratorial silence prior to their accusations against Susanna, as related in the Septuagint (LXX) or anagignoskomena Book of Daniel: 13. In an incident related by both the Roman historian Livy (Titus Livius Patavinus) and his Greek counterpart Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Lucretia, the loyal wife to Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus, was raped by Sextus Tarquinius, the third and youngest son of the last King of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. The dramatic Lucretia’s suicide (1541) by Enea Vico (1523-67) captures the moment immediately before the stoic Roman matron dies by her own hand, after telling her father and husband how she came to be defiled. This event (c.508 BC) is credited with inspiring the revolution that overthrew the monarchy and established the Roman Republic.

Christoffel van Sichem, the elder (1546-1624), the patriarch of a family of printmakers, completed his woodcut Judith with the head of Holofernes (c. 1600-10) after a painting (now lost) by Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617). The stalwart, pious and beautiful widow declared, “Listen to me. I am about to do something that will go down through all generations of our descendants” (Book of Judith, 8:32), and certainly countless artists would agree with that assessment. Here Judith has emerged from the tent of the Assyrian general, his headless corpse still emitting blood, as the maid stands ready with a sack for the trophy of her mistress. Another woman whose anger found its mark was (Marie-Anne) Charlotte de Corday (d’Armont) (1768-93), to whom the writer Alphonse de Lamartine (1790-1869) devoted a book of his Histoire des Girondins (1847),and gave the posthumous nickname “l’ange de l’assassinat (the Angel of Assassination)”. Corday was a member of a minor aristocratic family who came under the influence of the Girondins, whose prominent politicians had been forcibly expelled from the National Convention, 2 June, 1793 by sans-culottes activists for their alleged ‘counter-revolutionary’ activities.

Pieter Claesz Soutman (Dutch, c. 1580-1657), after a painting (1616-18) by Sir Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577-1640), Sennacherib, King of the Assyrians (c. 1636), (detail) etching; second state, sheet 37.9 x 47 cm, (Gift of Dr. J. Orde Poynton, 1959).

Corday believed that the revolution was being hijacked by extremists, leaving France vulnerable to invasion and civil war. The personification of these excesses, she felt, was Jean-Paul Marat (1743-93), a journalist and radical Jacobin whose faction had played a leading role during the Reign of Terror (1793-94). Corday gained entry to Marat’s home claiming to have knowledge of a planned Girondist uprising. Owing to a debilitating skin condition, Marat conducted most of his affairs from his bathtub, and it was there that Corday stabbed him in the chest. Printmaker, painter and draughtsman Pierre Louis (‘Henri’) Grevedon (1776-1860) produced portrait likenesses of famous political and society figures, and his Charlotte Corday (1823) came at a time of strong royalist and anti-revolutionary sentiment. Despite Corday’s position as a ‘radical’, her actions in murdering Marat made her story suitable for pro-royalist propaganda, as a courageous woman who sacrificed herself for France. At her trial Corday was unrepentant, saying, “I knew that he [Marat] was perverting France. I have killed one man to save a hundred thousand”. It did not save her, however. Corday was convicted and guillotined the same day, 17 July, 1793, four days after Marat was killed. Another virtuous but ultimately expendable French heroine, Saint Joan of Arc (c.1412-31), features in Jeanne au secours du roi (Joan of Arc coming to the aid of the king) (1656). It is one of several plates Abraham Bosse (c.1602-76) produced for Jean Chapelain’s poorly received epic poem La Pucelle ou la France délivrée (The Maid of Orléans, or France Delivered) (1656).

Criminals and degenerates who prey on he innocent and naïve appear throughout the works of satirist and social critic William Hogarth (1697-1764). Hogarth achieved widespread recognition for his sequential series of works addressing moral issues and the consequences of depravity. A Harlot’s Progress began as a series of six paintings in 1731, sadly destroyed by fire at politician William Beckford’s Fonthill House in 1755. They survive as engravings (1732), and depict a young woman, Moll Hackabout, who arrives in London from the country seeking employment as a seamstress, but becomes a prostitute. Her arrival in London (1732) shows the notorious and pox-ridden brothel-keeper Elizabeth Needham inspecting the young woman before her inevitable downfall.

William Hogarth (English, 1697-1764), Cruelty in perfection (1751), (Plate 3 from series The four stages of cruelty, 1751), engraving; third state, plate 38.5 x 32 cm, sheet 66.6 x 47.5 cm, (Purchased, 1995).

The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751) warns against immoral behaviour and society’s neglect of the underprivileged and indigent. By explicitly addressing the impact of the cycle of impoverishment, betrayal and brutality in the life of the fictional Tom Nero, Hogarth seeks to remind those in power of the easy progression from childish thug to abuser and convicted murderer in the absence of intervention. Having encouraged his pregnant lover, Ann Gill, to rob and leave her mistress, Nero then murders Gill when she meets up with him. Cruelty in perfection (1751) shows Nero being apprehended at the scene, the goods Gill had stolen lie on the ground beside her; her neck, wrist and index finger are almost completely severed. The text beneath the plate reads,

To lawless Love when once betray’d.

Soon Crime to Crime succeeds:

At length beguil’d to Theft, the Maid

By her Beguiler bleeds.

Arguably the most captivating, malevolent, capricious, utterly narcissistic, destructive and non-conformist figure in the history of art and ideas is the Devil himself; Satan the fallen, Beelzebub, the dragon, the ancient serpent, Shaitan, the arch-manipulator, the architect of war and dissent on earth. “Satan rises again in the exhibition, appearing in many deceitful guises. This prince of darkness, originator of evil, is the ultimate villain; conversely he is also a charismatic, radical figure”, Stone comments. The arresting engraving Several demons (1575) by Cherubino Alberti (1553-1615) is derived from the Sistine Chapel fresco

![Cherubino Alberti [called Borghegiano] (Italian, 1553-1615), after detail from the Sistine Chapel fresco The Last Judgement (1536-41) by Michelangelo (di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni) (Italian, 1475-1564), Several demons (1575), engraving image 31.1 x 20.9 cm, sheet 32.5 x 21.5 cm, (Gift of Dr. J. Orde Poynton, 1959).](http://troublemag.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/melbs_site02.png)

Cherubino Alberti [called Borghegiano] (Italian, 1553-1615), after detail from the Sistine Chapel fresco The Last Judgement (1536-41) by Michelangelo (di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni) (Italian, 1475-1564), Several demons (1575), engraving image 31.1 x 20.9 cm, sheet 32.5 x 21.5 cm, (Gift of Dr. J. Orde Poynton, 1959).

John Martin (1789-1854) was a Romantic painter, engraver and illustrator commissioned by the American publisher Samuel (Septimus) Prowett to illustrate John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667) in 1823, which resulted in forty-eight mezzotint engravings produced between 1823 and 1827. The almost science fictional element visible in Satan presiding at the Infernal Council (1825) looks not too dissimilar from a cosmic TED talk, where his throne sits atop a black sphere apparently floating within the space. It bears a resemblance to the artist’s earlier work Belshazzar’s Feast (c. 1821), depicting the Biblical episode from the Book of Daniel, which won the prize for Best Picture when exhibited at the British Institution in February, 1821. Here we see the debate amongst Satan’s ‘Stygian Council’ in the chamber of ‘Pandæmonium’ (at the beginning of Book II of Paradise Lost). A rotunda is filled with throngs of adoring acolyte fallen angels gazing upwards at their semi-nude and strident leader who is crowned and robed.

Another interpretation of Paradise Lost, this time by Charles Grignion, the elder (1721-1810), after a design by Francis Hayman, RA, depicts the prideful, vain and envious angel departing from the gates of Hell for his flight through Chaos. Sin and Death free Satan from Hell (c.1749-60), show Satan’s daughter Sin, portress of the gates, accompanied by her ‘Hell hounds’. Her offspring Death, clutching his spear and wearing a coronet, looks on admiringly as the door is rent aside. Der Tod als Erwürger (Death as the slaughterer) (1851), a confronting work by Alfred Rethel (1816-59), alludes to the cholera epidemic that ravaged parts of Europe in the early 1830s. Musicians flee in dread from the gallery of a gracious home, clutching their instruments, when Death crashes the function. He mocks the guests by playing his bone violin as he coolly stalks the floor: a dark, destructive force subduing all in his wake. The work serves to illustrate the stark dichotomy of the verses from Sirach (41:1-2),

O death, how bitter is the thought of you

to the one at peace among possessions,

who has nothing to worry about and is prosperous in everything,

and still is vigorous enough to enjoy food!

O death, how welcome is your sentence

to one who is needy and failing in strength,

worn down by age and anxious about everything;

to one who is contrary, and has lost all patience!

Hendrick Goltzius (Dutch, 1558-1617), after a painting (1588) by Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem (Dutch, 1562-1638), The dragon devouring the companions of Cadmus (1588), engraving; first state, image (sheet trimmed to image) 25.1 x 31.7 cm, (Gift of Dr. J. Orde Poynton, 1959).

Radicals, Slayers and Villains is the inaugural exhibition following the refurbishment of the gallery space, which pays tribute to the generous benefactor for whom it is named. Mrs Noel Shaw (née Henderson) completed a Diploma of Social Studies at Melbourne in 1942, and maintained a life-long association with the University. In 2011 she made a substantial gift for the redevelopment of the Baillieu Library, but died in March the following year before work was completed.

A participant in White Night Melbourne in February with her work The Skies Are On the Ground (2014), and the Melbourne Music Video Festival in March, artist Freya Pitt has contributed Between This Breath and the Next (2014). Using images taken from the selected prints, the three-minute digital animation screens in an ante-room adjacent to the Gallery. Andrew Brown has also produced an animated piece using material from the exhibition which plays in the main space.

To coincide with the annual Melbourne Rare Book Week (17-27 July, 2014), the Baillieu will be borrowing a copy of the two-volume Gutenberg Bible from the John Rylands Library at the University of Manchester. This particular copy was acquired from the dispersal, in 1892, of the famous library at Althorp, the Spencer family seat in Northamptonshire, assembled by collector and Whig politician George John Spencer, 2nd Earl Spencer (1758-1834). Spencer has his own connection to Australia, as First Lord of the Admiralty (1794-1801), when Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820) used his influence to convince him of the importance of an expedition to chart the coastline of New Holland.

As a result, Captain Matthew Flinders (1774-1814) was given command of the Investigator and set sail in January, 1801. (Spencer Street in Melbourne, and formerly the station, was named for John Charles Spencer, the third Earl (1782-1845), Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1830 to 1834).

Another ‘radical’ who irrevocably changed the world, Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (c.1395-1468) was the first person to create moveable type in the 1450s, and the practical system which allowed the mass production of printed books. Since that time, the print medium has been a powerful tool for the proliferation and dissemination of ideas, particularly those espousing a radical political, religious or social viewpoint. Gutenberg’s inventions sparked the information revolution that would lead to the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, after which ‘knowledge’ became so much harder for those in authority to stifle. Acclaimed for its high aesthetic and technical quality, the Gutenberg Bible (also known as the 42-line Bible) survives in forty-eight substantially complete copies, one of which will be arriving shortly. The exhibition, In the Beginning: Gutenberg’s Bible, will be displayed in the Dulcie Hollyock Room on the Ground Floor (18-27 July, 2014).

Radicals, Slayers and Villains, Noel Shaw Gallery, First Floor, Baillieu Library (Building 177), The University of Melbourne, Swanston Street, Parkville (VIC), until 3 August 2014.

University of Melbourne Cultural Collections – unimelb.edu.au/culturalcollections

Melbourne Rare Book Week – rarebookweek.com

Artist site – freyapitt.com

Radicals, Slayers and Villains will tour to three regional galleries in Victoria, beginning at the Art Gallery of Ballarat (25 October, 2014 – 18 January, 2015) – artgalleryofballarat.com.au

Inga Walton is a writer and arts consultant based in Melbourne who contributes to numerous Australian and international publications. She has submitted copy, of an increasingly verbose nature, to Trouble since 2008. She is under the impression that readers are not morons with a short attention span, and would like to know lots of things.

Submit a Comment